Work Orders That Close Themselves: From Request to Proof-of-Work Without the Fire Drills

In many operations, a work order is born in chaos and dies in ambiguity. It begins as an email, a hallway conversation, a scribble on a whiteboard “the conveyor is squealing again,” “that pump is running hot,” “the labeler is skipping every fourth print” and it ends when someone decides, usually by feel, that the problem is probably solved.

In between, the ticket ricochets among departments: maintenance asks for photos and gets a paragraph; purchasing orders parts that arrive without labels; production wants to know who’s coming and when; quality insists on a sign-off, but nobody attached the only photo that mattered. Everyone is busy, nobody is dishonest, and yet the work order reads like a cliffhanger with the last page missing. The irony is that the job itself may take fifteen minutes; what devours the day is the ping-pong of missing information.

The alternative starts at the very first click. A request should capture the truth planners actually use, not the free-text lore that will be re-explained three times later. When the requester selects a real asset from a real tree site, building, room, cabinet, bin the system already knows where the job lives, who owns it, and what else is nearby. When impact and urgency are chosen from a short, well-defined list safety, regulatory, throughput, cosmetic the scheduler understands the stakes and negotiates time on the right terms. The right intake, surprisingly, is short. It refuses poetry and demands proof: a photo of the leak, a twenty-second voice note describing the sound, a part number if the label is legible. The point is not bureaucracy; the point is to prevent the boomerang that quietly steals hours from five people across two shifts.

Planning then becomes a craft of minutes, not meetings. A planner should decide three things fast: who, what, and when. “Who” is not a person; it is a skill electrical, mechanical, controls that the system will resolve into a human based on availability. “What” is a kit: the predictable fasteners and labels that always run out at the worst time, plus the specific part or tool template the job calls for. “When” respects production’s reality: the earliest window that won’t break a line, the rule that calibrations precede audits, the policy that hot work sits behind permits. In a good system, missing parts don’t stall planning; they trigger a reservation or a purchase suggestion, and the work order keeps moving toward a start, not back to someone’s inbox.

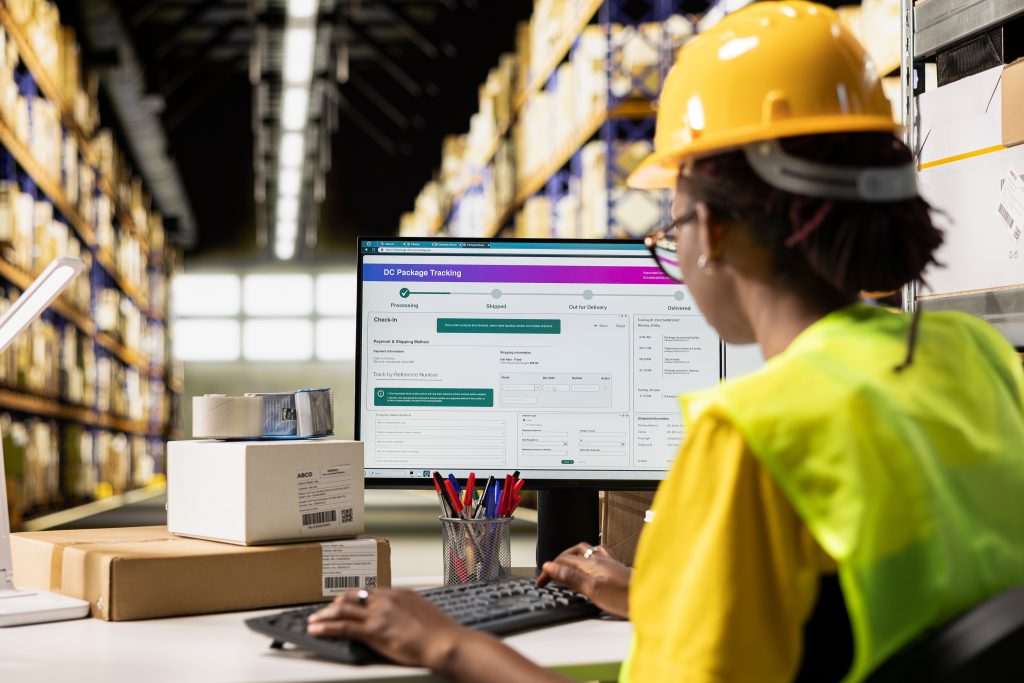

Staging is where software meets floor and either becomes useful or becomes a promise. If the technician must trek across the building twice to fetch a gasket or a label, the work order didn’t just waste time; it leaked credibility. A proper staging bin has a label that reads like a boarding pass work order code, asset, earliest start, responsible team and an actual, physical kit that anticipates the little things: zip ties, wipes, the exact calibration sticker, the tag to return the salvaged part to stock. If the job lives far from the tool crib, a portable kit travels with the technician; if the job will generate waste or require a functional test, the supplies are there. Staging is the part of the story that turns “we’ll try” into “we’re ready.”

Execution should record itself. The technician scans the staging label and the asset, and the checklist appears, not as a wall of text but as a thin thread of steps with thresholds. The point is to be unmistakable: “Measure motor current; it must be below 2.0 A.” The moment the technician taps “Pass,” the reading is captured with the unit; if it fails, the system proposes the likely causes and offers to convert the work order into a corrective job with the right parts and a new due date. Before and after photos live inline with the steps where they matter. The parts that leave the kit decrement stock by scan, not by memory. Time flows from the scan-in and scan-out, not from a handwritten guess half an hour later. Execution is thus a set of small, undeniable facts; no one has to write a novel at the end to prove something happened.

Closure is a landing, not a shrug. When the steps and evidence exist, the summary writes itself: who did what, at which asset, with which parts, for how long, to what result. The requester’s sign-off becomes a fast link, not a hunt for someone between meetings. If a bypass was installed, the system opens a follow-on ticket to remove it; if a temporary label was applied, a second ticket ensures it’s replaced with the durable one. A smart team even saves learning objects: a sixty-second annotated clip showing the trick that future technicians will forget under pressure. Work orders that close themselves don’t just document work; they multiply competence.

Governance and metrics matter because they prevent the quiet decay that turns good intentions into folklore. clocks should be real clocks: a task is late not because someone feels impatient but because an SLA says so, and late tasks must choose a reason parts, access, coordination that feeds improvement. Handoffs are gates, not hopes: planning cannot mark “ready” without a reservation; quality cannot sign until the photos and readings exist; production cannot accept without the test that actually proves throughput returns. If a job runs thirty percent over its standard time, the system asks for a short, factual root cause. Week to week, a team reviews not a sea of numbers but a handful of stories that those numbers reveal: the recurring asset that hints at a bigger failure pattern; the label that peels in cold rooms and fools scans; the aisle whose cycle route is thirty minutes too long and therefore two weeks overdue.

This approach makes people outside maintenance feel the change. Customer service stops asking “is it back up?” and starts quoting a timestamp. Purchasing sees consumption in the same system that scheduled the job and orders accordingly; finance sees the labor and parts against the right cost center without triangulating three spreadsheets. Quality and safety trade memory for evidence and arrive at audits with quiet confidence. It isn’t that forms became stricter; it’s that the system asked for the right information at the right time and paid it back with proof no one has to debate. The work order didn’t become heavier; it became lighter because it stopped boomeranging.

Underneath, this is a philosophy about friction. You remove it in design so you don’t have to manage it in crisis. You refuse to let people invent information twice. You make the most important action the easiest action: scan, attach, mark, close. Set the stage, and the job records itself. Solve the job, and the evidence writes itself. Close the job, and the story teaches itself. The hardest parts of a work order are the ones we used to think were human problems. They were design problems all along.